I moved to Lebanon this August to join the faculty of ACS at Beirut, after having spent six years teaching in Istanbul. At the recommendation of Dr. Fadi Skeiker, Professor of Theatre at the University of Jordan, the Lebanese NGO 961 – Art Factory invited me to teach drama workshops with young Syrian refugees. The workshop was a part of the national outreach phase of the Karama Beirut Human Rights Film Festival, which took place in Beirut last May. The theme of the festival, “The Others,” afforded me a way to enter these communities. Living abroad has provided me ample opportunities to explore the role of an outsider.

On Saturday, September 24th, we drove to the Beqaa Valley, nearly two hours northeast of Beirut and an hour and a half west of Damascus. The following day, we traveled south for an hour and a half to Nabatiyeh, which is 30 kilometers from the Israeli border. These were collaborations with the UN Peacebuilding Project and local NGOs. A week later we were hosted by the Success and Happiness NGO, which works with the EU and the Lebanese Red Cross, in Wadi Khaled, a long-impoverished area along the northern border of Lebanon.

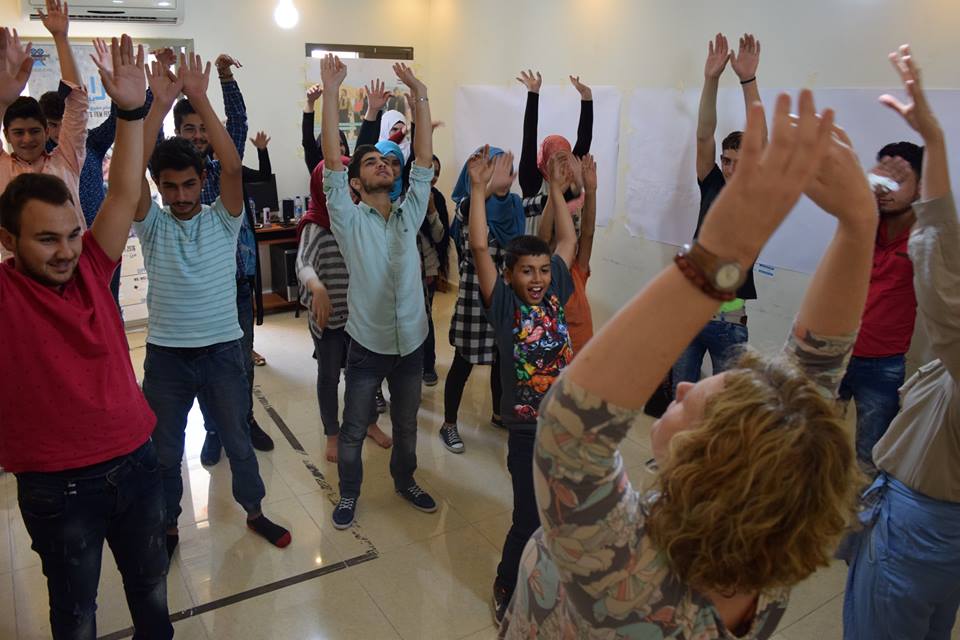

Haytham Chamass, director of the film festival and founder of 961 – Art Factory, suggested beginning the workshops with “ice-melting” exercises. I prefer that to “ice-breakers.” I modified a name and gesture game, community mapping exercises, and tableau work for each population, and then diverged from or extended the activities once the basic interpersonal dynamics at each center became clear.

After lunch, each group viewed the short film Transit Game, by Anna Fahr, in which a pair of Palestinian refugees, a young boy and girl, help a Syrian man who has driven into Lebanon to find a new home for his family. After the film, I gave the participants colored markers and asked them to write words and/or draw images that related to the film on white paper we’d taped up on the walls around the room, and to consider the theme of the film festival, “The Others,” as they were drawing.

Najwa Kondakji, an actor and the project coordinator for the film festival, translated my words to the participants, and Zena Takieddine, an author and Islamic Arts scholar, translated the participants’ words to me.

The fourteen Syrian participants in Beqaa ranged in age from 4 to 14. I kept the tone light and playful since most of them were very young. As I began an exercise related to birthdays, Zena explained that the Islamic calendar is different from the Gregorian calendar. We opted for tableaux using seasonal images. They drew pictures of what they observed in the tableaux. In groups, they taught each other games, and then we did the Arabic version of the Hokey Pokey.

They drew pictures of the characters from the film and of the man’s car, and they wrote that it was wrong when the little boy stole a piece of candy. After our group farewell, a volunteer at the center pulled me aside and pointed at a drawing of a family. He told me that the father of the boy who drew it is in prison in Syria. Then he pointed at a drawing of a house. The family finished building their house in Syria and had to leave before they moved into it.

The participants in Nabatiyeh were mostly teens and young adults: eight Lebanese boys, nine Syrian girls, and four Syrian boys. The Lebanese were Shia, and the Syrians were Sunni. It had taken a lot of community dialogue to bring these groups together. Although some of the young women are already married, and at least one is already a widow, they aren’t allowed to leave their houses. I’m not clear whether this is for safety or for religious reasons; however, the Lebanese woman running the center has been an activist since the 1970s, and she found a way to make this happen for her community. The young women are not allowed to touch men. There we were: the twenty-one participants, two translators, the film crew, representatives from the UN and NGOs, and me, all in one room. Somehow these young people from polarized communities were going to work together without any physical contact. When we arrived, they were sitting in lines on opposite sides of the room facing each other. Five hours later they were in two mixed-gender groups. One group created a scene of “Friendship” and the other group created a scene of “Welcome.”

The participants in our final workshop were teenage and young adult Syrian and Lebanese boys and girls who already knew one another. At the end of the workshop, two young men felt comfortable enough to share their stories.

The first young man, who was Lebanese, was in a wheelchair due to a condition from birth, I believe. He was sent to an orphanage for classes, while his eight brothers went to the local school. He convinced his father to let him go to the local school, and he was the only one of the nine boys to graduate. He hung his diploma prominently in the family home and then went on to earn a degree in accounting.

The second young man explained that he and his family had to leave Syria before his senior year of high school. Upon arriving in Lebanon, they stayed for two months in a small room with two other families. Each family had a corner. He took some computer courses, and became bored after that, so someone recommended that he volunteer at the center. Now he is in his second year of study to become a land surveyor.

We need another word for “refugee.” I found no synonym to describe the young people I met during this project appropriately. We need a word that brings to mind images of people who face the unknown with courage, remain hopeful in the face of brutal injustice, and enrich our communities with their stories.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Dyane Stillman.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.