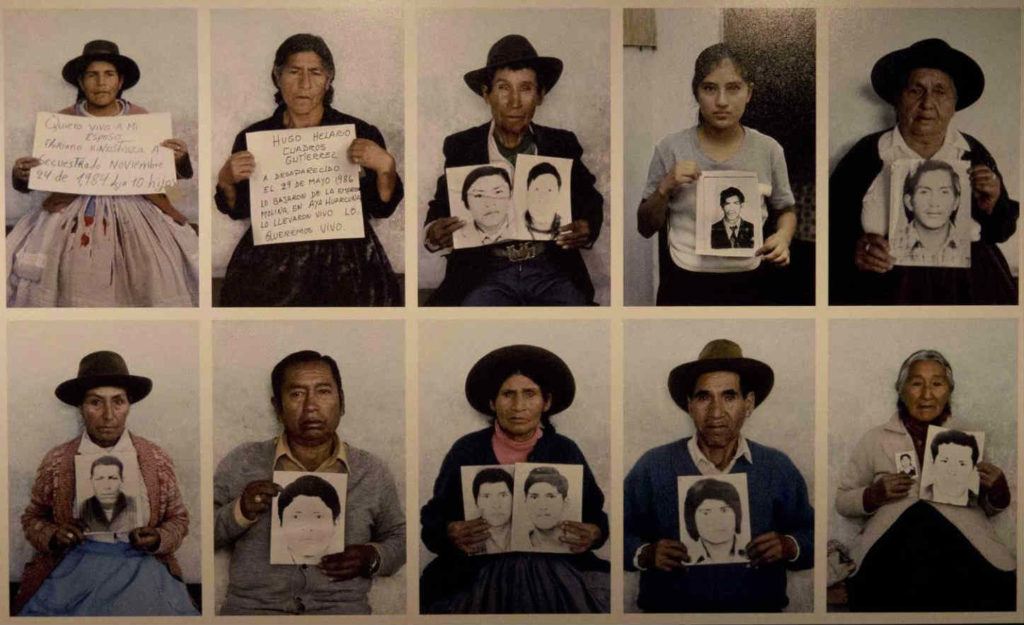

Family members look for their disappeared relatives after twenty years of political violence. Image via NoticiasSer.pe

The former Peruvian president Valentín Paniagua convened the Comisión de Verdad y Reconciliación/Truth and Reconciliation Committee (CVR) in 2001 after his predecessor Alberto Fujimori’s fall from power in 2000. Paniagua’s transitional government set in motion a process to adjudicate the abuses that occurred throughout twenty years of internecine warfare and political violence. Known as the time of the Shining Path insurgency (1980-1993) and Fujimori’s increasingly authoritarian rule (1990-2000), the epoch produced upwards of 70,000 dead and disappeared persons. [1] The CVR funded public art projects to entice people to testify about events they had witnessed or experienced during these years known popularly throughout Peru as “los años de violencia política.” Mark R. Cox has referred to these years as the time of “Pachaticray,” a Quechua word signifying “the world, upside down.” This Quechua term harkens back to the first to describe political violence in this manner, Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, the colonial chronicler. [2]

The CVR commissioned Peru’s famous contemporary theatre group, Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani, to produce public works of theatre and performance art that would tell stories of loss, violence, and mourning in an attempt to embolden Peruvians to share their stories with the commission.

Critics have reported about Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani’s involvement in providing support for the CVR, but little documentation exists recording the efforts of other theatre groups from the interior provinces of Peru that also produced public performance art in the aftermath of the fall of Fujimori’s dictatorship. [3] De pie sobre el espejo / Standing on top of a Mirror (2005) by Cusco’s Grupo Impulso de Teatro is one such example. Even though Impulso’s work outdates the time of the CVR by two years, it demonstrates patronage to the artistic process of remembering that the commission supported.

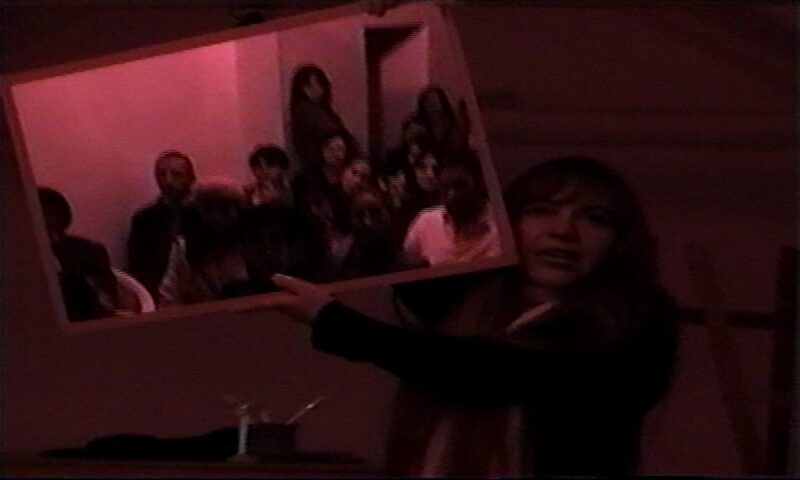

Tania Castro Gonzáles holds a mirror to the audience. Still image from De pie sobre el espejo, courtesy of Tania Castro Gonzáles.

Directed by the father/daughter team of Lucho Castro and Tania Castro Gonzáles, Cusco’s Grupo Impulso de Teatro is a theatre group that has existed for more than three decades in the provincial capital. A commitment to indigenous Andean culture and the dissemination of indigenous discourses that reinterpret Peruvian sentiments of nationalism informs Impulso’s work. Impulso has produced the famous colonial-era drama Ollantay, historical reenactments commemorating the founding of the Inca Empire, and works in tribute to José María Arguedas. Tania Castro Gonzáles is also renowned throughout Peru for her storytelling ability and holds audiences captive with her unique ability to conjure up different voices with her flexible range of expression.

The actresses welcome the audience into their ‘home.’ Still image from De pie sobre el espejo, courtesy of Tania Castro Gonzáles.

De pie sobre el espejo played on the role of the visualization of the house as a mnemonic tactic for organizing memories, better known as the method of loci, that the ancient Greeks and Romans used to teach memory recall. To begin the work, Castro Gonzáles prompts the audience to enter the converted colonial-period church by asking them to consider it a home where “les provoca ser, les provoca estar”/”you are provoked to be (exist), you are provoked to be (be present)”, thus playing on the two verbs in Spanish that signify different ways “to be.” Throughout the work, the audience-participants walk through the church in which each room, much like in the style of the tableau vivant, displays a scene portraying a distorted reality.

A macabre scene depicting madness and loneliness. Still image from De pie sobre el espejo, courtesy of Tania Castro Gonzáles.

Impulso sought to produce in De pie sobre el espejo what would be best described by Sigmund Freud as the unheimlich, the uncanny, but in a way that did not pinpoint certain events in Peru’s colonial and contemporary history. Instead, Impulso focused on replicating feelings of angst, despair, loneliness, sorrow, and mourning through these abstract scenes to weave together a Peruvian history in which all periods exist in one, linked by these sentiments. The group used poetic interludes accompanied by string musicians to inspire reflection with Castro Gonzáles holding a mirror to the audience in one room/scene and asking them to contemplate death and how it represents the infinite.

An actress portraying a dead woman speaks about the violence that killed her. Still image from De pie sobre el espejo, courtesy of Tania Castro Gonzáles.

Giving the spectators the ability to walk through the performance empowered them to become active participants in the work and enabled them to communicate with one another in a way that traditional, staged theatre does not allow. One can imagine that, as perspectives toward the events of two decades of warfare and repression still divided the nation, the abstract would have provided a more effective catalyst for promoting social cohesion than a realistic portrayal of specific events.

An actress portrays the shipment of African slaves on boats. Still image from De pie sobre el espejo, courtesy of Tania Castro Gonzáles

During the 2000s, Peru’s dramatists revisited the painful years of political violence and repression that culminated at the end of Alberto Fujimori’s reign. Few theatre groups in Peru have made the documentation of their public performance works from this period accessible to the general public, leaving a gap in how historians and culture workers contextualize the epoch. Any endeavor to make such records public would be valuable to critics and artists throughout the world who work in using art to spur testimony and heal past traumas.

An actress dances the festejo, an Afro-Peruvian dance in a scene depicting freedom from slavery and the foundation of a Creole culture in Peru. Still image from De pie sobre el espejo courtesy of Tania Castro Gonzáles.

[1] Peru. International Center for Transitional Justice and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Anexo 2. “¿Cuántos peruanos murieron? Estimación del total de víctimas causadas por el conflicto armado interno entre 1980 y 2000.” Comisión de Verdad y Reconciliación. Lima: Comisión de Verdad y Reconciliación, 2003. Print.

[2] Cox, Mark R., ed. Pachaticray: Testimonios y ensayos sobre la política y la cultura peruana desde 1980. Lima: Editorial San Marcos and Centro de Estudios Literarios Antonio Cornejo Polar, 2004. Print.

[3] See A’ness, Francine. “Resisting Amnesia: Yuyachkani, Performance, and the Postwar Reconstruction of Peru.” Theatre Journal 56.3 (Oct. 2004): 365-414. Print.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mary Barnard.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.